The Tale of Two Irenes: White When Needed

Miss Irene had two identities under federal records: one white and one Black.

Miss Irene had two identities under federal records: one white and one Black. As a naturalized citizen, Irene married a white man 12 years her senior in 1919 named Paul at the age of 18. In 1920, the census reported Paul as the head of the household, Irene as his spouse, and a 3-year-old girl named Lula as his sister. Everyone was listed as white. By 1924, Irene would be divorced from Paul and married to a Black man named Charles. By then, Irene would identify as Black. Even more strikingly, 1927 would end the second marriage to Charles and list Lula as a daughter, not a sister.

Throughout my dissertation, I am very critical of the Detroit Urban League and describe the organization as an invasive entity seeking to control the Black public identity through social work. But the Detroit Urban League is more to the interwar Black community than I write. I explain how the Jewish Social Service Bureau has the staff and finances to spend more time with their clientele. In addition, Jewish Detroiters are not facing the same public crisis as Black Detroit, so patience, connection, and friendship are more present in JSSB’s social work cases, which can span 100s of pages while overworked DUL social workers are limited to a notecard. In both communities, DUL and JSSB are viewed as organizations their respective communities can turn to when in crisis. Irene was one of those clients in the Detroit Urban League records.

In April of 1920, Irene contacted the DUL in request of “fare to her sister’s home in Chatham, Ontario.” DUL gave her two dollars and “advice concerning divorce.” The 20-year-old found herself in a sensitive situation. She was pregnant and the father was not her 30-year-old white husband, Paul. DUL so aptly wrote, “the girl is colored, husband white, father of the child is colored.” In a previous case, a husband contacted the DUL to investigate his wife suspecting her was having an affair and social workers mediated between the two. In this interracial marriage, the husband was in a peculiar predicament; which organization could he use? The Detroit Urban League also had a peculiar response: no contact with the husband for reconciliation. In all these cases, the social worker would talk to all parties involved but this one had a swift solution; the young woman would divorce her current husband and marry the father of the child. There was no push back to her plan nor any reconciliation efforts that usually occurred. The case notecard wrongly listed the 3-year-old child, Lula, as both her and her husband’s. Public records listed the 3-year-old child as Irene’s sister, Lula.

There are many possible reasons why the Detroit Urban League went against their normal procedure of mediation with a married couple. Her commitment to marry the father of the child may have resolved the concern of financial dependence so mediation was not needed. The Detroit Urban League’s exclusive dealings with the Black community put the social workers in uncharted territory. The interracial aspect may have created a sensitivity that the organization was unwilling to approach. I want to argue the Detroit Urban League avoided mediation as to not disclose she was Black. Federal records all categorized Irene as white. If the Detroit Urban League had intervened, her husband may have found for the first time he married a Black woman. There could have been many negative outcomes from this revelation that could reach the public sphere and create more tension for Black citizens. It could also endanger the life of Irene. Despite Irene’s initial contact in 1920 seeking a divorce, she and her husband would not divorce until September of 1924. It is unknown how they reconciliated but Paul, her husband, initiated the divorce and listed “cruelty” as the cause for divorce. The divorce decree listed zero children.

More confusedly, public records had Irene marrying her child’s father, Charles, the month before the divorce was granted. Charles, Irene, and child were listed as Black. The child once listed as sister was revealed to be their daughter Lula and the previous marriage begins to make more sense. As discussed in my dissertation, marriage allowed women to either escape or enter the cycle of poverty. At the time, single motherhood almost guaranteed a cycle of poverty unless the women had familial financial help. Irene married Charles, a machinist at one of the auto factories, for financial stability. It is unknown if Paul knew the child was Irene’s and agreed to report to the census that Lula was a sister. One could also argue that Lula’s white passing time was limited, and Irene needed to lie about her whiteness, her child, and marry a breadwinner to survive. Charles, Lula’s father, always reported to the census he was Black. When they married, all three of them would identify as Black. In 1920, Irene was not pregnant. Charles, the father of Lula, was the person she truly wanted to marry. She would technically be a bigamist for a month in 1924, married to both Paul and Charles under two different races. Three years later, she would file divorce from her second husband due to “non-support.” Alimony was granted. Irene would marry again. Throughout her life, Irene and her immediate family would slip in and out of the white category depending on their location but in the end, Irene would continue to report her and her child’s Blackness.

“Why Detroit?”: A Dissertation Connecting the Past & Present

Why does my work on Detroit matter?

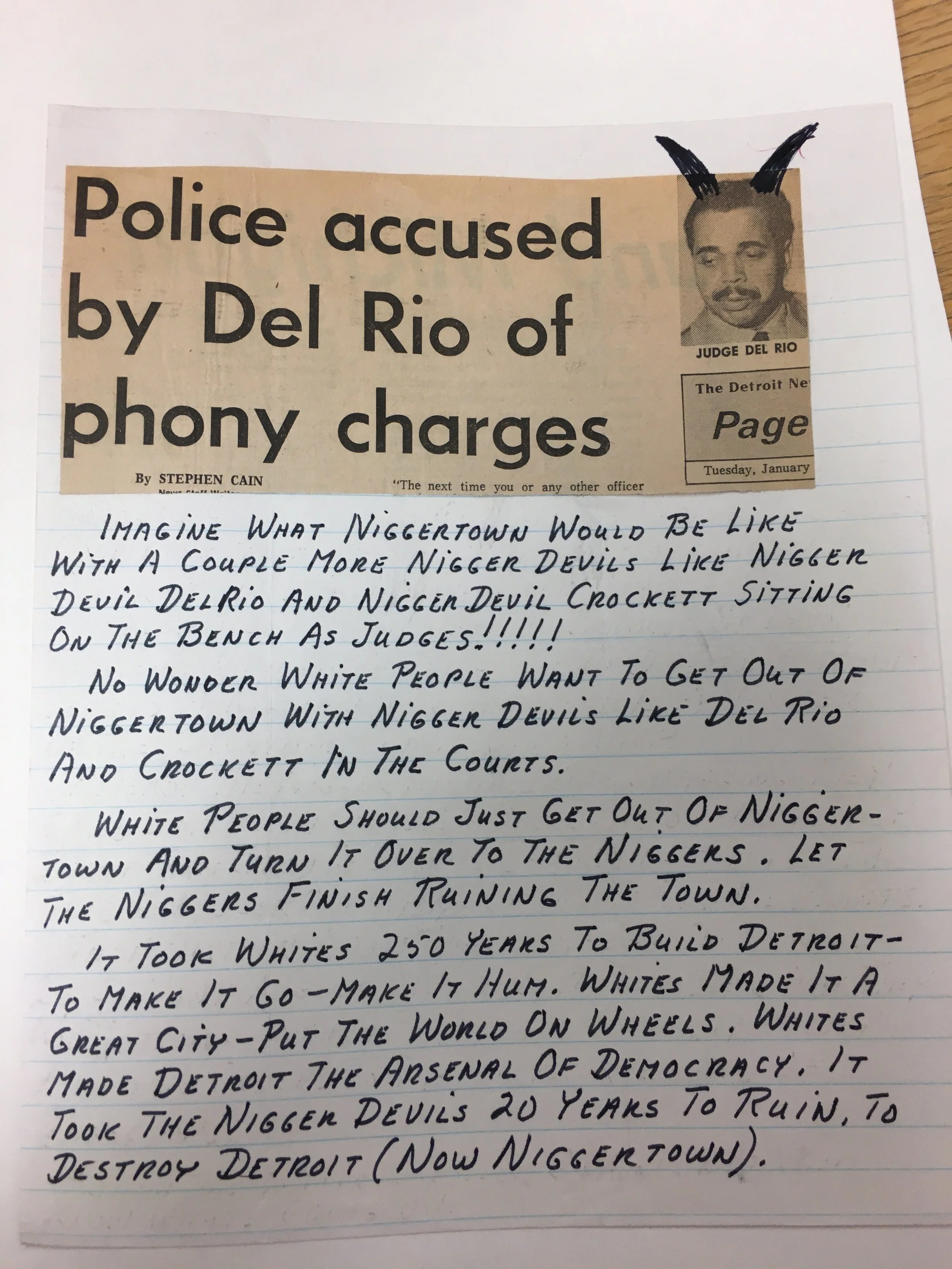

In 1973, the above hate letter was sent to the Detroit Urban League regarding two African American judges who had recently been covered in the Detroit News for challenging the police in their handling of heroin cases and separately, accusing them of police brutality. Judge James Del Rio accused two officers of perjury and beating of a Detroit citizen. He dismissed the case of an assault of an officer by stating “It has long been a habit of the Police Department of the city of Detroit to have a situation where they beat up a person and then come to court and charge him with assault and battery to head off any civil suits.”[1] An article right beside Judge Del Rio’s read “Crockett wants purity tests in heroin cases.”[2] Judge George W. Crockett Jr. postponed “all heroin cases in his courtroom until the Detroit Police Scientific Section” started performing purity tests of the heroin. He believed that Detroit citizens were overcharged in cases of heroin as well as marijuana compared to citizens of Grosse Pointe, a white suburb, because of the lack of purity testing. Judge Crockett asked “Why is it that in the inner city, in the ghetto, they bring these marijuana cases in as felonies?”[3] His question of marijuana cases carried over to heroin as only low level dealers were brought into court with grams but police “hardly ever arrest the man dealing in pound and kilogram amounts.”[4]

Judge James Del Rio and George W. Crockett Jr. speak more to modern conceptions of prison reform and the Black Lives Matter movement in this news coverage. My project focuses more on the derogatory response that followed. Specifically, the last line of the hate letter declaring African Americans destroyed Detroit, a city that “took whites 250 years to build.”[5] Nationally, Detroit has been perceived as a fallen industrial city and the face of the blame has continually been the African-Americans who have remained. Six years before the above hate letter, the 1967 Detroit Rebellion occurred which was sparked and mostly sustained by conflict between African American residents and the Detroit Police Department. Following the rebellion, Detroit became even more racially polarized as the city’s old age issues of school segregation and redlining came to the forefront in politics. More white citizens moved into the suburbs and Detroit’s racial make-up shifted yet again as African American population steadily increased as white population dramatically decreased. But this nativist tinged hate letter and racist assessment of Detroit has origins decades earlier.

Fear and anxiety of Black migrants destroying the city of Detroit originated in the 1910s as a response to the dramatic population increase. World War I’s demand for Black industrial workers in industrious cities like Detroit triggered these mass population movements of Black men, women, and families. From 1910-1920, Detroit’s Black population increased by 611 percent. A Black population of 5,741 became a population of 40,838 largely as a result of the migration of southern working-class Blacks. By 1930, Detroit’s Black population had increased by another 194 percent to 120,066.[6] As a response, the city and social service agencies created a system to monitor and police these migrants for decades to prevent them from becoming dependent on state aid.

The anti-Black characterizations have persisted in modern day coverage of the state of Detroit. During the 1910s, African Americans were not the only group causing fear and anxiety. Jewish immigration caused an uproar throughout America and the fear led to the 1924 Immigration Act, which imposed a strict quota on Eastern European immigrants directly affecting Jewish immigration. Detroit’s Jewish immigration grew “1000 in 1800 to 10,000 in 1900, and 34,000 in 1914, with Russian Jews constituting over 75% of the total.”[7] Detroit gives a unique midwestern perspective where one can explore the construction and instability of whiteness studying how the city and social service organizations pathologized and treated Black southern migrants and Eastern European Jewish immigrants.

My dissertation project explores this interwar period and connects the statistical propaganda to today’s view of Detroit and its Black citizens. The intracommunal war for control of these racialized identities in the public sphere tell a story of politicization of private family lives in the journey to achieve racial uplift.

[1] Stephen Cain, “Police accused by Del Rio of phony charges,” The Detroit News (Detroit, Michigan), January 23, 1973.

[2] Stephen Cain, “Crockett wants purity tests in heroin cases,” The Detroit News (Detroit, Michigan), January 23, 1973.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Research Reports, Undated, Correspondence Undated, box 65, Detroit Urban League Records, Bentley Historical Library.

[6] U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census (Washington, D.C.): Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910: Manufacturers, VIII, 84; Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920: Manufacturers, VIII, 19; Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930: Population II, 728.

[7] Robert Rockaway. "Moving in and Moving Up: Early Twentieth-Century Detroit Jewry." Michigan Historical Review 41, no. 2 (2015): 59-79. Accessed January 27, 2020.