“Why Detroit?”: A Dissertation Connecting the Past & Present

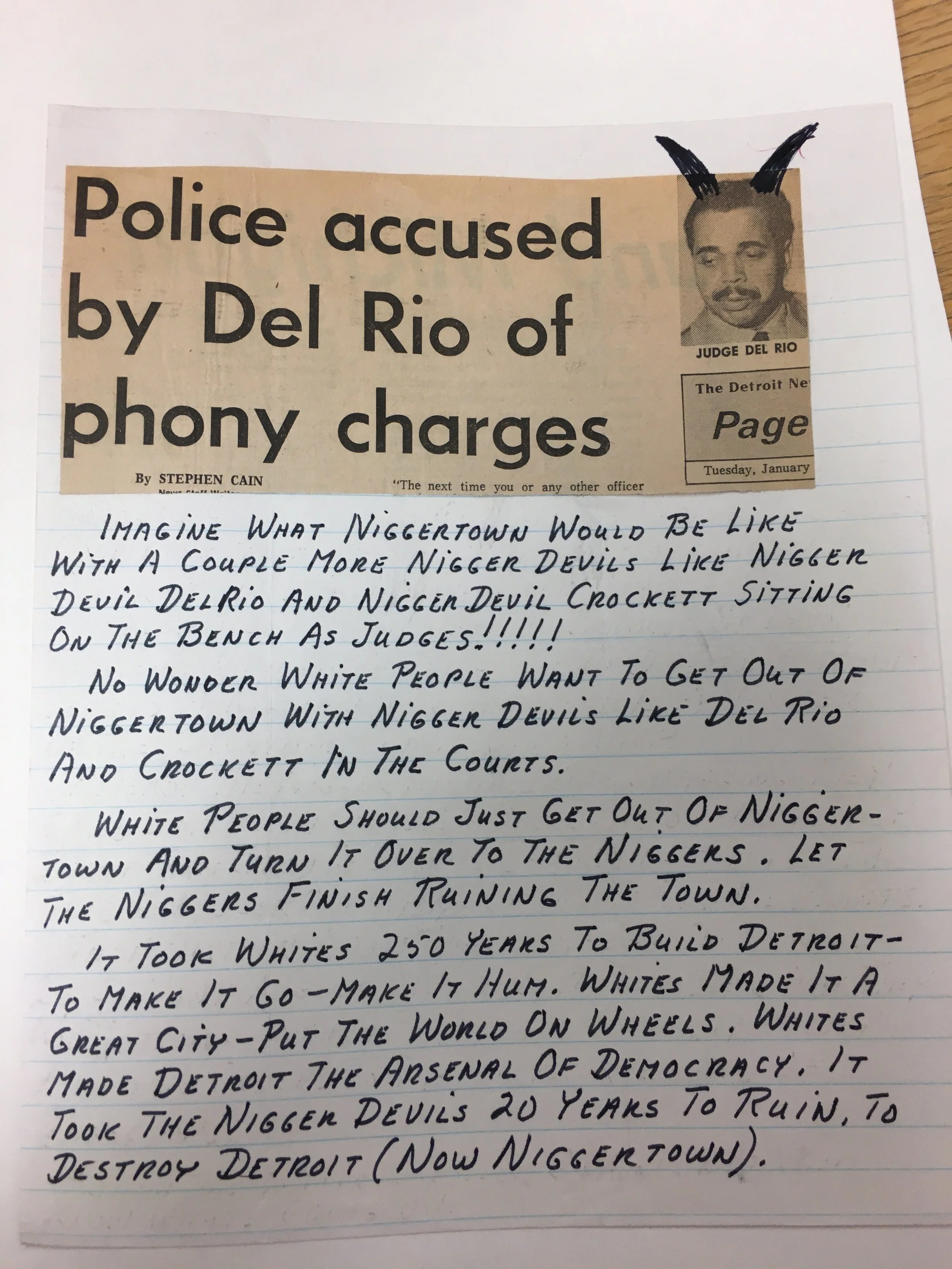

In 1973, the above hate letter was sent to the Detroit Urban League regarding two African American judges who had recently been covered in the Detroit News for challenging the police in their handling of heroin cases and separately, accusing them of police brutality. Judge James Del Rio accused two officers of perjury and beating of a Detroit citizen. He dismissed the case of an assault of an officer by stating “It has long been a habit of the Police Department of the city of Detroit to have a situation where they beat up a person and then come to court and charge him with assault and battery to head off any civil suits.”[1] An article right beside Judge Del Rio’s read “Crockett wants purity tests in heroin cases.”[2] Judge George W. Crockett Jr. postponed “all heroin cases in his courtroom until the Detroit Police Scientific Section” started performing purity tests of the heroin. He believed that Detroit citizens were overcharged in cases of heroin as well as marijuana compared to citizens of Grosse Pointe, a white suburb, because of the lack of purity testing. Judge Crockett asked “Why is it that in the inner city, in the ghetto, they bring these marijuana cases in as felonies?”[3] His question of marijuana cases carried over to heroin as only low level dealers were brought into court with grams but police “hardly ever arrest the man dealing in pound and kilogram amounts.”[4]

Judge James Del Rio and George W. Crockett Jr. speak more to modern conceptions of prison reform and the Black Lives Matter movement in this news coverage. My project focuses more on the derogatory response that followed. Specifically, the last line of the hate letter declaring African Americans destroyed Detroit, a city that “took whites 250 years to build.”[5] Nationally, Detroit has been perceived as a fallen industrial city and the face of the blame has continually been the African-Americans who have remained. Six years before the above hate letter, the 1967 Detroit Rebellion occurred which was sparked and mostly sustained by conflict between African American residents and the Detroit Police Department. Following the rebellion, Detroit became even more racially polarized as the city’s old age issues of school segregation and redlining came to the forefront in politics. More white citizens moved into the suburbs and Detroit’s racial make-up shifted yet again as African American population steadily increased as white population dramatically decreased. But this nativist tinged hate letter and racist assessment of Detroit has origins decades earlier.

Fear and anxiety of Black migrants destroying the city of Detroit originated in the 1910s as a response to the dramatic population increase. World War I’s demand for Black industrial workers in industrious cities like Detroit triggered these mass population movements of Black men, women, and families. From 1910-1920, Detroit’s Black population increased by 611 percent. A Black population of 5,741 became a population of 40,838 largely as a result of the migration of southern working-class Blacks. By 1930, Detroit’s Black population had increased by another 194 percent to 120,066.[6] As a response, the city and social service agencies created a system to monitor and police these migrants for decades to prevent them from becoming dependent on state aid.

The anti-Black characterizations have persisted in modern day coverage of the state of Detroit. During the 1910s, African Americans were not the only group causing fear and anxiety. Jewish immigration caused an uproar throughout America and the fear led to the 1924 Immigration Act, which imposed a strict quota on Eastern European immigrants directly affecting Jewish immigration. Detroit’s Jewish immigration grew “1000 in 1800 to 10,000 in 1900, and 34,000 in 1914, with Russian Jews constituting over 75% of the total.”[7] Detroit gives a unique midwestern perspective where one can explore the construction and instability of whiteness studying how the city and social service organizations pathologized and treated Black southern migrants and Eastern European Jewish immigrants.

My dissertation project explores this interwar period and connects the statistical propaganda to today’s view of Detroit and its Black citizens. The intracommunal war for control of these racialized identities in the public sphere tell a story of politicization of private family lives in the journey to achieve racial uplift.

[1] Stephen Cain, “Police accused by Del Rio of phony charges,” The Detroit News (Detroit, Michigan), January 23, 1973.

[2] Stephen Cain, “Crockett wants purity tests in heroin cases,” The Detroit News (Detroit, Michigan), January 23, 1973.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Research Reports, Undated, Correspondence Undated, box 65, Detroit Urban League Records, Bentley Historical Library.

[6] U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census (Washington, D.C.): Thirteenth Census of the United States, 1910: Manufacturers, VIII, 84; Fourteenth Census of the United States, 1920: Manufacturers, VIII, 19; Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930: Population II, 728.

[7] Robert Rockaway. "Moving in and Moving Up: Early Twentieth-Century Detroit Jewry." Michigan Historical Review 41, no. 2 (2015): 59-79. Accessed January 27, 2020.